The idea for writing about graffiti began as a result of my annoyance with seeing how so many properties are defaced by those who have no regard for other people’s property. Each day as I travel through my Bushwick neighborhood, I am appalled at all the despoiled graffiti I see of buildings, mailboxes, scaffolding, and even a

church! As angry as I get every time I see what I feel is vandalism in the form of graffiti, I must say, that I have learned a little more where I now see a distinction between people’s perception of what is considered art and what is not.

There is a lot more to graffiti than what offends the eye, so I felt it necessary to provide some historical background to put things into perspective. For me, what I consider art is not what I see as I walk to the train station each day in my neighborhood. What I saw is an eyesore!

However, I am prepared to discuss the many facets of graffiti, good and bad. Let’s begin with defining graffiti.

Defining Graffiti

Graffiti, seen as a form of visual communication, usually involving illegal and unauthorized marking of public space by an individual or group, is a stylistic symbol or phrase spray-painted on a wall by a member of a street gang. Please know that not all graffiti is gang-related. Graffiti can be understood as antisocial behavior done in order to gain attention or as a form of thrill-seeking, but it also can be understood as an expressive form of art.

According to Section 145.60 of the New York State (where I reside) legislation Penal – part 3, title 1, and for the purpose of this section, the term “graffiti” means the etching, painting, covering, drawing upon, or otherwise placing of a mark upon public or private property with the intent to damage such property. In addition, the legislation also indicates that no person shall make graffiti of any type on any building, public or private, or any other property real or personal owned by any person, firm or corporation, or any public agency or instrumentality, without the express permission of the owner or operator of said property; making graffiti a class a misdemeanor. Let me note that the law does not, however, draw a clear distinction between great works of street art that have been thoughtfully applied and the casual tagging of a wall.

So, now that definitions have been provided, let’s take a little journey into the history of Graffiti in the United States.

History of Graffiti in the United States

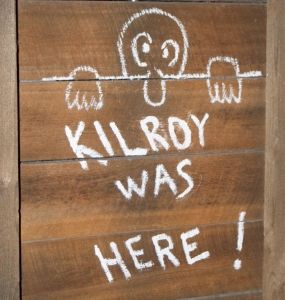

Graffiti has a long history of being a tool for protest. Because of its public form, it inherently makes a statement to a broad audience of passersby. During World War II, it became popular for soldiers to write the phrase “Kilroy was here” along with a simple sketch of a bald figure with a large nose peeking over a ledge, on surfaces along their route. It was their “tag” catalyzed by the invention of the aerosol spray can. Early graffiti artists were commonly called “writers” or “taggers” (individuals who write simple “tags,” or their stylized signatures, with the goal of tagging as many locations as possible).

to a broad audience of passersby. During World War II, it became popular for soldiers to write the phrase “Kilroy was here” along with a simple sketch of a bald figure with a large nose peeking over a ledge, on surfaces along their route. It was their “tag” catalyzed by the invention of the aerosol spray can. Early graffiti artists were commonly called “writers” or “taggers” (individuals who write simple “tags,” or their stylized signatures, with the goal of tagging as many locations as possible).

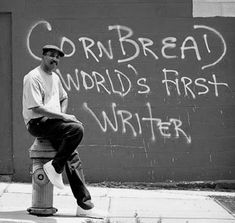

In America around the late 1960s, graffiti was used as a form of expression by political activists, and also by gangs such as the Savage Skulls, La Familia, and Savage Nomads to mark territory. Towards the end of the 1960s, the tags—of Philadelphia graffitists, Darryl “Cornbread” McCray, Cool Earl, Sketch, and Topcat 126 started

to appear. In 1965, Cornbread now widely considered the world’s first modern graffiti artist, was a 12-year-old troublemaker housed at Philadelphia’s Youth Development Center (YDC). In the belly of a Philadelphia juvenile corrections facility, Cornbread passed the time by adding his unique signature to the facility’s walls, which, until then, had been covered exclusively in gang names and symbols. Cornbread spent day and night hunting for fresh spots, scrawling his newly-acquired moniker on nearly every surface in the YDC. Not long after, many graffiti writers took hold of the trend and graffiti began to spread.

The Heart and Soul of New York City

The tagging of signatures was quickly sweeping through cities nation-wide. It was no surprise that a parallel 1960’s graffiti movement was developing in New York City. Taki 183, a self-described bored teenager from Washington Heights, a Greek neighborhood just north of Harlem, created his now-iconic tag in 1969 by combining “Taki,” a diminutive form of his Greek name, Demetrius, and “183,” his street number. Around 1970-71, other graffitists followed adding their street number to their nickname.

Soon after, graffiti began appearing on city surfaces, subway cars and trains became major targets for New York City’s early graffiti writers and taggers to be seen by a wider audience. Branding train cars with their signature tag were ways of letting the subway take it all around the city building their fame. The subway rapidly became the most popular place to write, with many graffiti artists looking down upon those who wrote on walls. What are your thoughts so far? Is it art or vandalism?

Graffiti: Art, Eyesore, or Vandalism?

Getting back to the purpose of this article, from the history of graffiti to present day, the writing has morphed from the subways into any blank space just waiting to be marked up. For me, it’s an eyesore that I consider vandalism based on the definitions previously provided for you. In my neighborhood, I see scribbling on the corner mailbox and the walls of storefronts. To be fair, there are places that have beautifully spray-painted murals. Then, you also see Black Lives Matter that someone spray-painted on the sidewalk or side of a building. This (BLM) is perceived to be better aligned with graffiti as an art movement.

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring

are but two artists who became famous due in large part to the graffiti art that they promulgated throughout New York City. Basquiat a Black man and Haring a gay man with HIV both marginalized artists created distinctive visual languages that took to the walls of New York City and let the people know of their struggles and hopes.

Final Thoughts

Given the monumental influence graffiti art has had on our popular culture, from music, film, and television to fine art, toys, and clothing, it’s easy to not know or to forget the form’s humble roots and remarkable evolution – I have learned the history as I researched for this article. Graffiti, consisting of the defacement of public spaces and buildings, remains a nuisance issue for cities. Even though many excite over graffiti art, it is also a highly contentious medium because it is technically defacement and vandalism, and thus it is often devalued.

What I see as vandalism of property became a teachable moment. The ugly sight of meaningless scribbling on things without permission, to me is still a problem, but I understand the modern graffiti street art – murals – that have emerged out of the spray paint cans of graffiti artists throughout history. That, I can appreciate.

Add comment